![]()

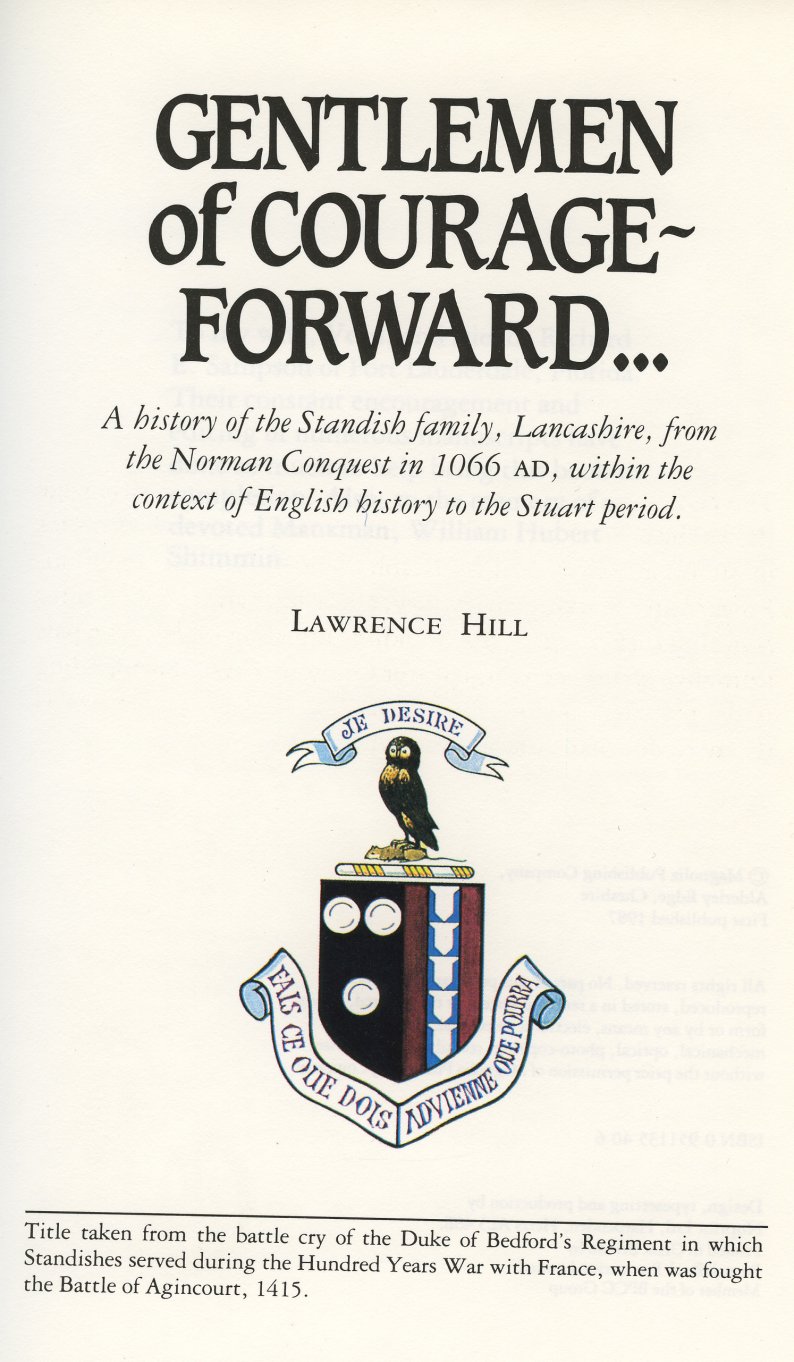

14. Author Lawrence Hill - Gentlemen of Courage ~ Forward.

Links -:

The Divorce of Thomas Standish of Ormskirk?

A 'younger son of the House of Standish’?

Myles Standish and his descent from the

Standish Family of Ormskirk by Lawrence Hill.

The importance of accurately delineating

family relationships for inheritance purposes is self-evident. – Lawrence Hill

The descent of the Standish family of

Ormskirk.

Another vital clue in a 1481 deed is that

William’s son, Evan, was of Weryngton (Warrington) and if the son was a

resident of Warrington it reasonably follows that his father was probably from

the same district. Moreover, recent research into Standish history by local

historians reveals that ‘a Warrington branch of the Standishes was formed in

the early fifteenth century by one Richard Standish, and in that family there

was a William who had a son named Evan (John)’. A deed of 1405—6 confirms these

findings. Whatever minor or reversionary claim Evan might have had on the

nucleus of the Ormskirk lands, probably as a cousin of Hugh, we do not know. A

further point reveals itself on this subject: if Hugh had been a descendant of

the Warrington branch, then one would expect such a name to have been used

earlier in the branch.

Hugh did have a definite relationship with

the Alice Standish who, as will shortly be

explained, was the original inheritor

of these vital lands. It is,

therefore, abundantly clear that the deed of 1481 covers a family matter

which was being settled at a late stage and that Hugh was not called on to pay

any consideration to others to validate finally his tenure of lands, which were

already ‘in his possession’.

We now turn

again to try to determine, once and for all, the true parentage of Hugh

Standish. Someone in that late period of the fifteenth century must have been

from the House of Standish and within reasonable, ancestral distance from his

birth date in 1584, for Myles to have known and insisted that he was descended from

that house, as shown in the concluding paragraph of his last will and

testament of March 7th 1655: ‘My great G(ran)dfather being a 2cond

or younger brother from the house of Standish of Standish’. It is

inconceivable that he would have made such a statement if it were not true. It

is maddening that he did not specify which ancestor was directly

connected, thereby leaving it for others to try to puzzle it out for hundreds

of years. Perhaps his son and heir, Alexander, knew and Myles thought a

recitation of it in his will would be redundant. In any case, this matter was

irrelevant to his claim to the estates which he felt had been fraudulently

‘detained’ and with which injustice he seems to have been preoccupied near the

end of a long and arduous life. The lands were, in fact, detained from his

great grandfather, Huan Standish, who was, in turn, the great grandson of Hugh

of Ormskirk.

The problem is to

determine from which first son and lord of Standish Manor the

Hugh in question might be descended. Although we know very well every first son

and lord, the task seems almost hopeless, for it could well have been, as

previously stressed, that a reference to the particular ‘younger son’ we are

seeking was never given in any deed or historical document. But we still have

evidence from our Standish pedigree that the name Hugh had been used several

times in the main line from as early as the thirteenth century.

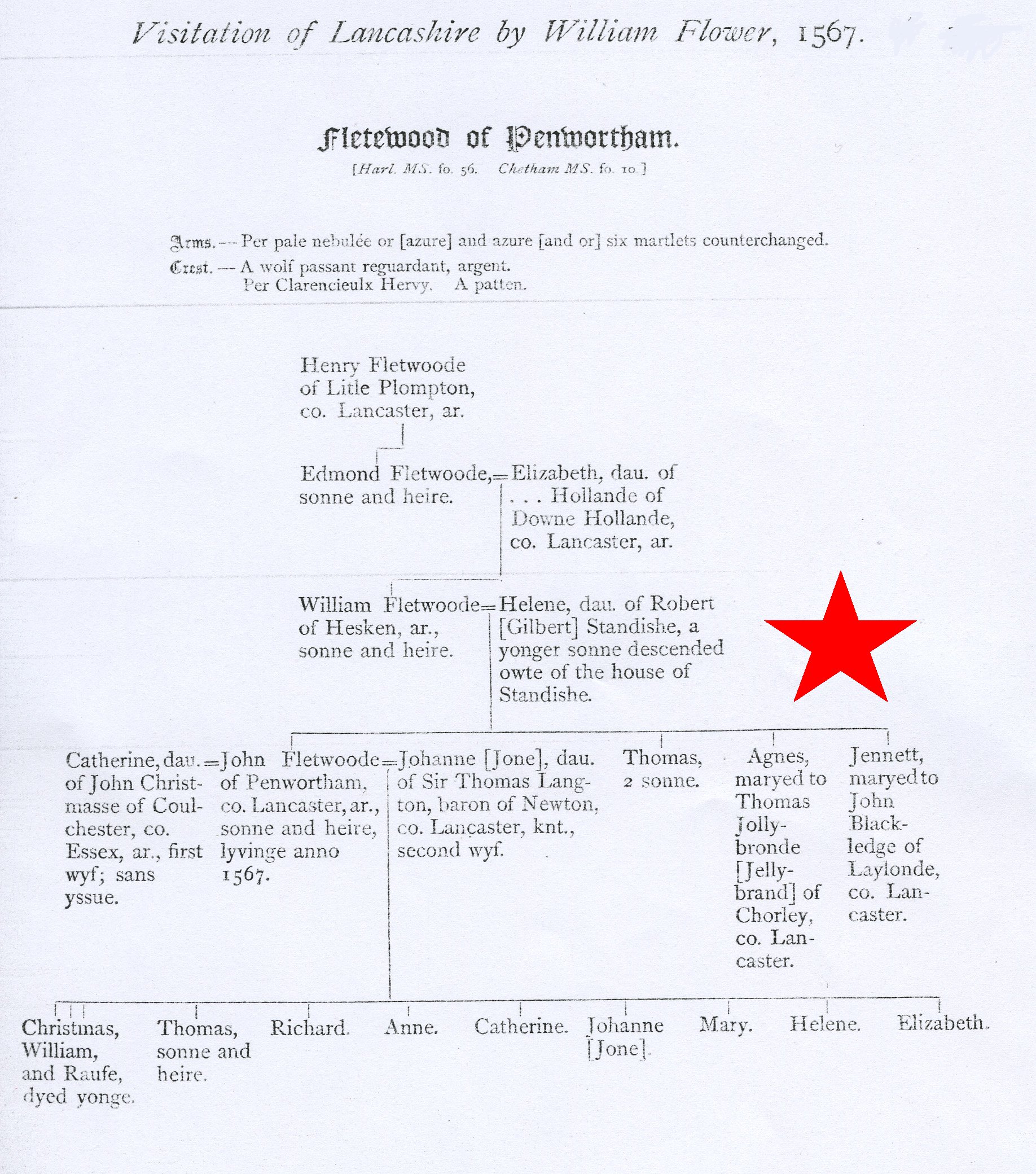

Very fortunately, a lead is provided in an

ancient document showing one result of a visitation of a Royal Herald, William

Flower, to Lancashire in 1567. It is surprising that the vital information

it contains has either been misconstrued or previously overlooked. The

pedigree provided for Flower by the Fletewood (Fleetwood) family for his

examination would have had to have been accurate and verifiable genealogically, since the right to display heraldic arms was

not approved lightly by the Crown, for many reasons.

The vital clue we are seeking is a notation

on the pedigree that Robert Standish, or his father Gilbert, is described as ‘a

younger son descended owte (out) the house of Standish’. This may be read as

‘descended from a younger son of the House of Standish’, and the similarity

with Myles’ statement in his will is an extraordinary circumstance.

Flower’s visitation was reasonably near in time for the facts concerning Robert

and Gilbert to be clearly known when the pedigree was prepared. Moreover, this

particular sequence of Christian names happens to be unique to the period in

question.

Since we also know that Hugh Standish was

Gilbert’s father (from Porteus, deeds 1 and 2, showing the descent of the same

lands through the same trustees) a painstaking search of

all Standish deeds eventually brought to light the important, albeit obscure,

evidence in the deed of 1468—9 as to Hugh’s parentage.

It is here that we find Hugh’s father identified, dating perfectly, as Alexander

Standish, Lord of Standish Manor in the years from 1434 to 1445. Hugh

Standish of Ormskirk, therefore, must be

the link to the House of Standish, which has been sought for centuries.

The source of the key nuclei of Ormskirk

lands is now also ascertained from the deed of 1423—24. They are identically

the same estates in question and must have descended by inheritance or gift to

Hugh from his aunt, Alice Standish Burscough. It will be seen that Hugh’s first

son, Gilbert, was named after Alice’s father. In the deed of 1481 it states

that these lands are ‘in the vills of Ormeskirke and Newburgh’

(Burscough and Lathom). The Burscough family were prominent landowners in the

Ormskirk area and the deed of 1423-4 undoubtedly constitutes a marriage

settlement by Catherine Burscough on her son, Richard, and Alice Standish,

which gained for the Standishes their first foothold into that locality. No

other Standish family owned such lands at that time and it is pertinent that,

in 1481, they appeared in the hands of a nephew, Hugh Standish.

In

the vitally important trust deed of 1540 (AMS deed no. 7), Thomas Standish, the

first son of Robert and the great grandson of Hugh, the first Ormskirk

Standish, granted to trustees all lands etc. held by him in ‘Burscough,

Wrightington, Newburgh, Mawdesley and Croston or

elsewhere in County Lancaster’, to hold for his use during his life and

afterwards for the use of his daughter Anne for five years. Then:

‘After the five years, they are to hold for

the use of the right heir of Thomas legitimately

begotten; in default for the use of John his brother and John’s legitimate heirs; in default

for the use of Huan, another brother of Thomas, and Huan’s heirs. Remainder to

the right heirs of Thomas’ (Italics by author).

Thomas seems to have had an unfortunate

life. He was less than nine years of age when he was married to Jane (or

Joanna) of the powerful Stanley family, whose seat was then nearby in Lathom. She was barely eleven. The child-marriage

was consummated in due course and at least two children were born, Ann and

Hugh. The latter is not mentioned in the 1540 deed so he must have been born

later than that. In 1558, Thomas and Jane were divorced by the Archdeacon of Richmond on the

grounds of having been under age when married. Under law, this had the sad

effect of making their heirs illegitimate. Ann and Hugh were thus ineligible to

inherit the named estates which, as stated, were then to revert to John

Standish, Thomas’s next younger brother, thence to his heirs. If John had no

issue then the estates were to pass to the next brother, Huan, the great

grandfather of Myles.

But, as

early as 1539, Thomas started selling part of the Ormskirk estates and becoming

indebted to William Stopford, a wealthy landowner in the area who was closely

connected with, or perhaps an agent of, the Earl of Derby. Thomas died about

1566 and his son,

Hugh, also began to fritter away the inheritance, which was not rightfully his.

This included not only the original properties which came down from the first

Hugh of Ormskirk but also extensive estates which had been the dowry of his

grandmother, Margaret Croft. William Stopford was again the buyer.

The

significance of these acts is that under the trust deed the estates were

entailed and, particularly for Thomas’s son, Hugh, to dispose of them, because

of the divorce, was tantamount to fraud. This apparent breach of trust was of

primary concern only to the reversionary heirs and by 1540 both John and Huan had settled in the Isle of Man where they may not

have realised what was going on, or had no effective means of contesting

the sales even if they did. Since he was probably unsure of the validity of his

titles, Stopford later took the precaution of obtaining releases of any claims

on the part of John, brother of Thomas, in 1572, and Jane, the divorced wife of

Thomas, in 1576 (AMS deeds 24 and 27). But he never obtained such a release from Huan. This is almost certainly the basis for Myles’ claim

in his will that he was fraudulently deprived of the Lancashire estates.

Now let us

suppose that John, Thomas’s brother, died without heirs, which seems to be the

case. By the terms of the 1540 trust the properties should then have reverted

to Huan, who had never relinquished any claims, or to his lawful descendants

including Myles. The estates, which had begun to be sold as early as 1539 were

largely gone by 1570. So for Myles’ son, Alexander Standish, to have

successfully pursued this tenuous claim some time after Myles died in 1656

(more than a hundred years after most of the property had been sold!), he would

have had to have proved all these facts. An English court would then have had

to have been induced to turn out the tenants then in possession, who were

undoubtedly innocent third parties who had received their titles in good faith

and for valuable considerations. Clearly this would have been an impossible

task. William Stopford had died in 1584.

His probable

employers, the Stanley family, who had been created Earls of Derby in 1485 but

had been, in fact, owners of the entire Isle of Man since 1405, continued there

in a viceroy-like capacity until as late as 1765, although they never lived on

the island.

The Isle of

Man occupies a strategic position in the Irish Sea, roughly equidistant from

England, Scotland and Ireland. It is about thirty miles long by ten miles wide

and is an island of bays and mountains of great natural beauty. The capital is

Douglas situated on the east coast and the Island’s position in relation to the

mainland of England can be seen in the maps provided. Peel Castle, on the west

coast, was known to have been used as a fortress retreat by the Stanley family

during the English Civil War in 1648.

Although

originally inhabited by Celts, from the eighth century onwards the Island was

raided and settled by Scandinavian Vikings, mostly from Norway. Vikings also

occupied and ruled the islands north of Scotland (Orkneys and Shetlands), the

northern part of Scotland itself and the Hebridean Islands on the western side

of Scotland. The latter islands were combined with Man to form the kingdom of

the Sudreys and ruled by kings of Norse descent under the over-lordship of

Norway. In the thirteenth century Scotland recovered the Hebrides and later

Norse suzerainty over Man lapsed. Scotland, in turn, finally relinquished Man

to England as one of the results of the wars of King Edward III against the

Scots.

When John

and Huan Standish went to Man, about 1540, they were therefore tenants of the

Stanleys, except for a short initial period before the monasteries were broken

up. ‘Huyn Standish’ was recorded as a tenant of Lezayre Abbey and paid an

annual rent of twenty-four shillings for the property known as the Ellanbane

estate. This name means ‘White Island’ in Manx Gaelic. Later, the rent became payable to the Stanleys and was reduced

over the course of time. Since the ultimate title was vested in the

Stanleys, this meant that the property, which is thought to have comprised

about 200 acres at the time, and with a substantial dwelling house, was held in

fee-tail and could thus only be inherited within the family and not be

bequeathed to others, mortgaged or sold. Ellanbane never functioned as a manor

as that system did not exist on the Isle of Man.

No doubt a

farm of this size provided a reasonably comfortable living, but the will of

John Standish, the son of Huan and grandfather of Myles, reveals only rather

meagre chattels — certainly nothing on the scale, which would have prevailed at

Standish Hall. Of course, the land and buildings were not included in the will,

since they could not be devised, and the thing of value which automatically

went to the lawful descendants was a perpetual non-transferable lease, with a

low, almost nominal, rent.

From Huan

onwards the line of descent has also been established. The author acknowledges,

with appreciation, the research into the Manx Standishes by G. V. C. Young,

O.B.E., of the Isle of Man, published in Pilgrim Myles Standish, First

Manx-American, 1984, and for that part of the pedigree in Plate ‘B’ p. 1,

in respect of Myles Standish’s father and grandfather.

So far as

can be ascertained, Myles was born in 1584 and had two younger brothers,

William and John. No facts for certain are known of his early life, but the

probability is that he attended school in Lancashire since the educational

facilities on the island were limited. It is thought that he might have

attended Rivington Grammar School, near Prescot in Lancashire (which still

exists), since Myles’ distant relative, Alexander Standish of Duxbury, was a

patron and had attended it himself. Myles, in his youth, may also have lived

with the Duxbury Standishes as his island home was rather remote, but this is

necessarily conjecture. Deeds do show that his father, John the Son, died

before 1602; that his grandfather, John the Father, died after 1603, and that

the Ellanbane estate passed into the hands of Myles’ younger brother, William,

some time after that. Since it could not

have done so if Myles were living, the

only logical conclusion to be drawn is that the executors presumed, or

were told, that Myles had died or was killed during the protracted Netherlands

campaigns. This possibility is suggested by G. V. C. Young based on his

research into sketchy medical records, which are still available in the Leiden

Municipal Archives. A ‘Myls Stansen’ is shown as having died in hospital there

on 1st November 1601 and this might account for an incorrect report

of his death. The records were kept by a Dutch-speaking clerk and are quite

irregular.’

When, and

if, he returned to the Isle of Man, Myles would have found William in

possession and he could then have certainly established his right as the lawful

successor. But the facts are that he either chose not to do so or did not

return. There remained one final opportunity to do this when he returned to

England from Plymouth Colony, America, for almost a year in 1625—26. Manx laws

at that time, which had descended from the Norse, provided for a statute of

limitations of twenty-one years on such a claim, so there might have been just

time to press it. Yet he evidently did not do so, nor is there any indication

that his descendants ever attached any particular importance to this part of

the claimed inheritance.

A final observation about his will is the absolutely accurate and

unambiguous naming

of the Ormskirk lands, after long years away from England. This is the most decisive and revealing

feature of the whole enucleation, for these properties had belonged only to the Ormskirk branch. Proof of Myles’ descent

from Huan Standish of the Isle of Man is further confirmed by the name

of the last estate mentioned in the will, ‘the ile of Man’, since no other descendant of Robert

Standish of Ormskirk ever held that property.

From our

pedigree giving the line of descent it may be seen that Hugh Standish of

Ormskirk had a brother named Robert, great uncles named Gilbert and Robert, and

a cousin named William. The name John, too, is prominent and all these

Christian names have come right down through Ormskirk and to the Isle of Man.

While there is no record of the name ‘Myles’ being used in the main Standish

line, it is known to be from the Celtic ‘Maolmhuire’ and may be found in early

Manx registers - Laurence

Hill

![]()

Author Lawrence Hill simply repeats the arguments made by G. V. C. Young, O.B.E., of the Isle of Man, published in Pilgrim Myles Standish, First Manx-American, 1984 regarding the descent of the Standish Family of Ormskirk and the theory that the Isle of Man was the birthplace of Myles Standish. The original arguments regarding the theory that the Isle of Man was the birthplace of Myles Standish came from the Reverend T.C Porteus in 1920.

“The author acknowledges, with appreciation, the research into the Manx Standishes by G. V. C. Young, O.B.E., of the Isle of Man, published in Pilgrim Myles Standish, First Manx-American, 1984, and for that part of the family pedigree in respect of Myles Standish’s father and grandfather”. - Lawrence Hill.

Lawrence Hill also makes a very important and vital statement in relation to the Will of Myles Standish -:

“The importance of accurately delineating family relationships for inheritance purposes is self-evident”. – Lawrence Hill

In pursuance of the above statement Lawrence Hill makes three points -:

(1) TheDivorce of Thomas Standish of Ormskirk in Lancashire.

(2) The Visitations of Lancashire in 1564.

(3) The Land referred to as the Isle of Man.

POINT 1. The Divorce of Thomas Standish of Ormskirk.

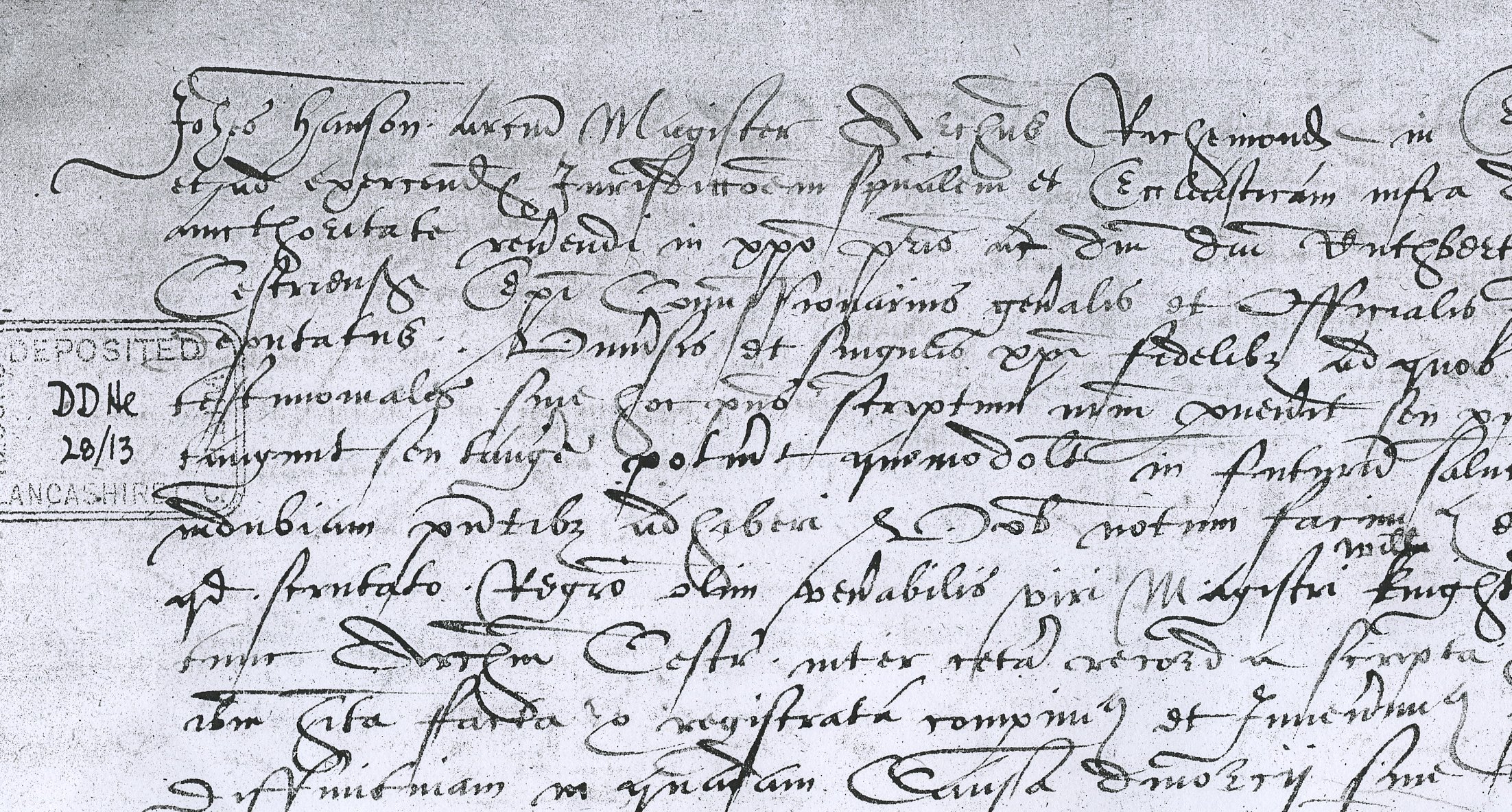

December 18th1539hester Consistory Court Depositions

“There was a doubt about the date of the divorce between Thomas Standish and Joan Stanley alias Standish; and it now transpires that the proceedings leading to the divorce took place in 1539, Depositions were entered on 18 December of that year and various local witnesses were called. After the child-marriage, Thomas Standish went into Man and there dwelt with his father Robert Standish, while the” woman” (10 years old) dwelt with her mother in Lathom”. – Reverend T.C. Porteus )

20th November 1558.

In 1558, Thomas and Jane were divorced by the Archdeacon of Richmond on the grounds of having been under age when married. Under law, this had the sad effect of making their heirs illegitimate. Ann and Hugh were thus ineligible to inherit the named estates, which, as stated, were then to revert to John Standish, Thomas’s next younger brother, thence to his heirs. If John had no issue then the estates were to pass to the next brother, Huan, the great grandfather of Myles. - Lawrence Hill.

The Church investigation into the Child marriage was conducted in 1539 in accordance with Canon Law. The question to be to be resolved was “ did the act of consummation take place whilst the children were under lawful age? The evidence given to the church court by several witnesses was that on completion of the marriage contract Thomas Standish returned to the Isle of Man with his parents and the bride Joan Stanley returned to Lathom with her parents and the marriage was not consummated until the children became of age. Thus the marriage was lawful under canon law and the Church could not divorce Thomas Standish and his wife Joan Stanley. Their son Hugh Standish was thus the lawful and legitimate heir of his parents. Nullity proceedings that bastardized the children require evidence that the marriage was consummated while the parents of the children were under age. - Webmaster

Lancashire County Archives ref: DDHE 28/13 date 20th Nov. 1558.

1. The Act Book and the Deposition Book of the Ecclesiastical Court at Chester have been searched without result for the divorce dated 20th of November1558.

-Reverend T.C.Porteus.

2. Fortune was evidently dogging the steps of Thomas Standish. He was parting with his estate, and moreover, if the Alleged Divorce Document refers to him? He was thus unhappy in his domestic life.

In 1558 (1548 is crossed out in Piccope’s transcript), this latter trouble reached its culmination; for on November 20 in that year John Hanson, M.A., Archdeacon of Richmond, pronounced sentence of divorce between Thomas Standish of Ormskirk parish and Jane (Joanna) Stanley, otherwise Standish, of the same parish. The reason given for the divorce was that Thomas was not nine years old and Jane not eleven years old when they were married.

This document is difficult to understand: surely it must be, in some way, an erroneous summary of the case. Child-marriages of the kind were often dissolved when the parties grew up and refused to ratify the arrangements of their parents; but a case of this kind, where they had lived together for nearly twenty years, and where there was issue, the Hugh afterwards mentioned, strikes one as suspicious. – Reverend T.C. Porteus

3. We can hardly think that the reason given for dissolving a juvenile and un-ratified marriage would be adduced, or would be deemed sufficient, in regard to the divorce of those who had co-habited for such a long period. – Reverend T.C. Porteus

So perhaps the Thomas of the divorce was not Thomas the father of Hugh, but a relative and, if so, it would follow that the Joan of the divorce was not Hugh’s mother Joan. – Reverend T.C. Porteus

4. Or is the alleged divorce document a forgery? – Reverend T.C. Porteus

5. A contemporary of Thomas Standish of Ormskirk gentleman, and perhaps a “ poor relation,” is mentioned in a deed belonging to Mr. James Bromley, of The Home Stead, Lathom, It appears thus in his library catalogue -:

“ 14 Oct. 3 and 4 Philip and Mary, 1557. * Indenture c lease between Peter Stanley of Biconstath, Esq., an Edward Standishe of Ormeskyke, ‘ corviser ‘ [shoemaker and Jane his wife, of londe, medow, and pasture in Orme-kyke called Awaynes Feld for 21 years. Rent: eightpence payable half-yearly.

Witnesses : William Pyle of Lyvepol Robert Byckerstythe of Byckerstathe, Thomas Jackson and Edward Standish of Ormskirk. – Reverend T.C. Porteus

Lawrence Hill quotes the Reverend T.C. Porteus on several occasions in his book. The fact that he does not included the research findings of the Reverend T.C. Porteus on the alleged divorce document in his book runs contary to his statement -:

“The importance of accurately delineating family relationships for

inheritance purposes is self-evident”. – Lawrence Hill

![]()

1564.

The year 1564 provides the

occasion and setting for the appropriate use of a Forged Divorce document as

highlighted by the Reverend T.C. Porteus in the court dispute between William Gerard of

Ormskirk, son and heir of Gilbert Gerard, deceased and Hugh Standish of

Ormskirk son and heir of Thomas Standish, deceased. The basis of William

Gerard’s legal case is that Hugh Standish is illegitimate and therefore not the

lawful heir of his father Thomas Standish. Consequently Hugh Standish has NO

right in law to the TITLE of the disputed property.

The court finds in favour of Hugh Standish recognising Hugh as the lawful son and heir of his father Thomas Standish and the rightful owner of the disputed property TITLE.

1564 Duchy of Lancs. Pleadings; Eliz. vol. 59 G 7 (2)

A further

reference to Thomas Standish and Hugh his son has also been found. In 1564 William Gerard of Ormskirk, son and heir of

Gilbert Gerard, deceased, complained

that whereas Thomas Standish of Ormskirk sold two messuages, eight cottages, and certain lands there and in

Burscough to Gilbert Gerard and his heirs about 30 Henry VIII (1538-1539), and they descended to William, who

placed there John Ireland and Richard Keykewiche as his tenants-at-will;

now certain deeds had come into the hands

of Hugh Standish who supposes himself to be son and heir of the

said Thomas, About four years ago he entered into the premises and indicted

William and his tenants for forcible entry, etc.

Hugh answers that his father Thomas Standish made a settlement of

his lands in Ormskirk,

Burscough, Wrightington, Newburgh, Mawdesley and Croston, the feoffees being Brian Morecroft and others. They

were to hold for five years after the death of Thomas, to the use of

Anne daughter of Thomas, and afterwards for the heir’s male of Thomas.

This was long before the conveyance to Gilbert Gerard, if any such conveyance was made. Afterwards Thomas died;

Anne died intestate in the life of

her father; Hugh became heir in tail by virtue of the remainder in the deed.

He was then and still is, under age,

viz. 19 years old.

1. Chester Consistory Court Depositions.

2. Duchy of Lancashire Pleadings; Eliz. vol 59 G 7.

![]()

Point 2. The Visitations of Lancashire 1564.

Very fortunately, a lead is provided in an ancient document showing one result of a visitation of a Royal Herald, William Flower, to Lancashire in 1567. It is surprising that the vital information it contains has either been misconstrued or previously overlooked. The pedigree provided for Flower by the Fletewood (Fleetwood) family for his examination would have to be accurate and verifiable genealogically, since the right to display heraldic arms was not approved lightly by the Crown, for many reasons. The vital clue we are seeking is a notation on the pedigree that Robert Standish, or his father Gilbert, is described as ‘a younger son descended owte (out) the house of Standish’. This may be read as ‘descended from a younger son of the House of Standish’, and the similarity with Myles’ statement in his will is an extraordinary circumstance. Flower’s visitation was reasonably near in time for the facts concerning Robert and Gilbert to be clearly known when the pedigree was prepared. Moreover, this particular sequence of Christian names happens to be unique to the period in question. – Lawrence Hill

Since we also know that Hugh Standish was Gilbert’s father (from Porteus, deeds 1 and 2, showing the descent of the same lands through the same trustees) a painstaking search of all Standish deeds eventually brought to light the important, albeit obscure, evidence in the deed of 1468—9 as to Hugh’s parentage. It is here that we find Hugh’s father identified, dating perfectly, as Alexander Standish, Lord of Standish Manor in the years from 1434 to 1445. Hugh Standish of Ormskirk, therefore, must be the link to the House of Standish, which has been sought for centuries. - Lawrence Hill

The “albeit obscure" conclusion by Lawrence Hill does not arguer well with his statement -:

“The importance of accurately delineating family relationships for

inheritance purposes is self-evident”.

– Lawrence Hill

![]()

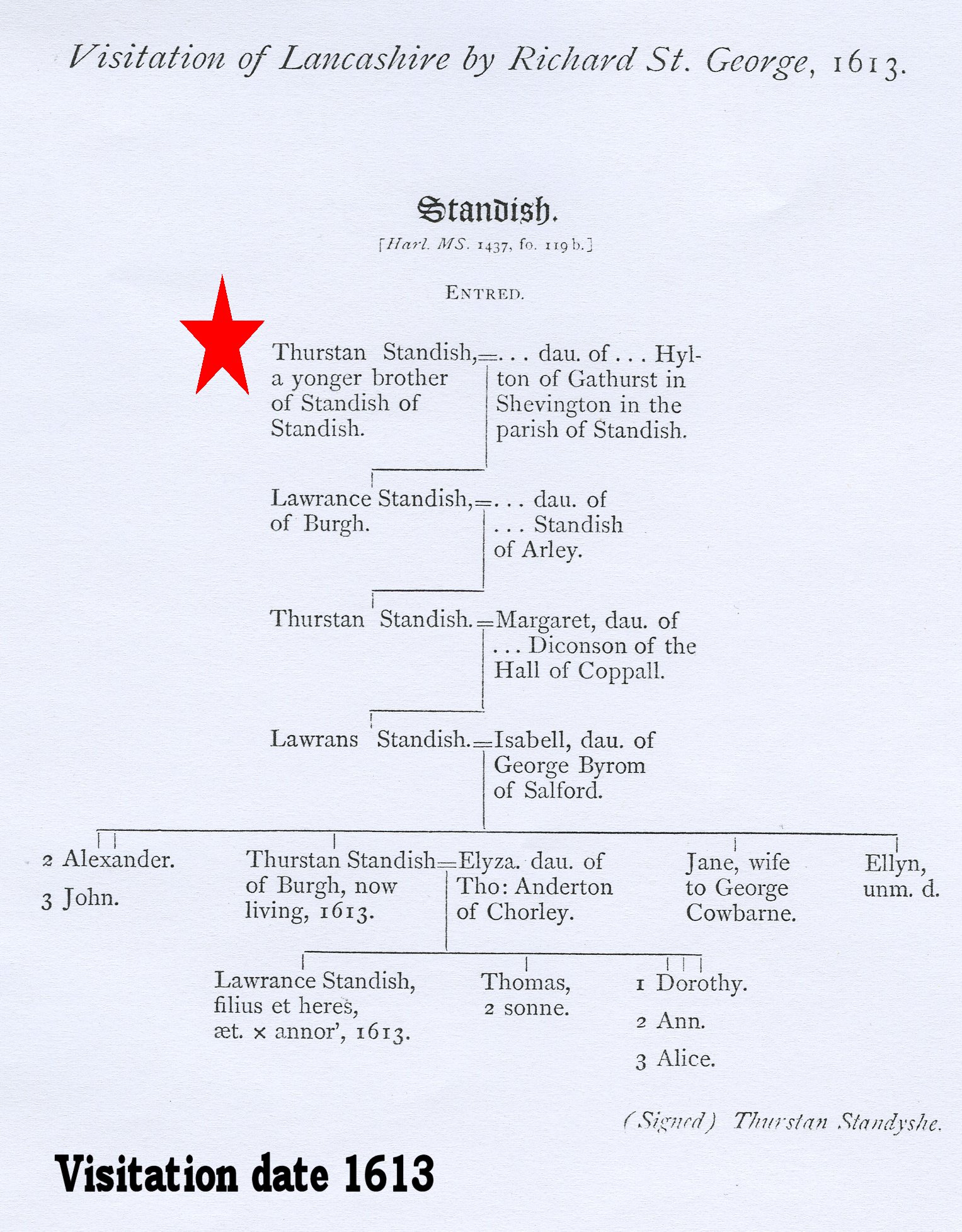

The Visitation in 1567 for the Fleetwood Family is not the only ancient Visitation of Lancashire that describes a member of the Standish family as stated below-

‘a younger son descended owte (out) the house of Standish’ – Lawrence Hill.

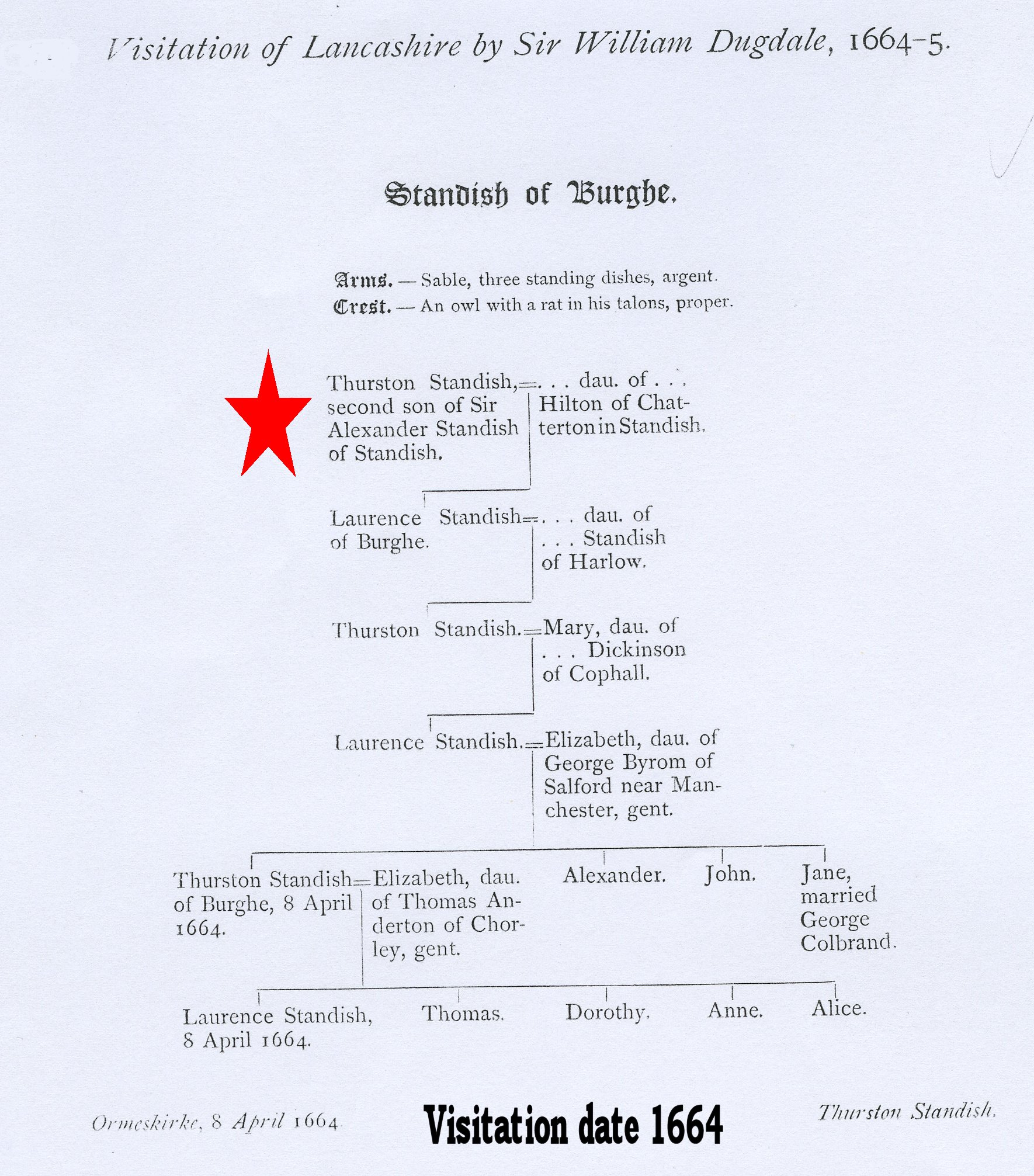

The Standish Family of the Burgh on the

ancient Manor of Duxbury Lancashire England are also descended from a second

Standish son. The Standish family of the Burgh are descended from the Lords of the Manor of Standish and they use the same Arms and Crest as the House of Standish. Their descent from the Standish family of Standish and

the House of Standish is recorded in the archives and documentation of the

Lords of the House of Standish. The Standish family of the Burgh were resident on

the Manor of Duxbury in 1584 the year Myles Standish was born. Myles Standish

named his own lands in America “Duxbury” and stated in his Will that his great

grandfather was a second son from the House of Standish, thus the Standish Family of

the Burgh also have a very close similarity with the statements in the Will of

Myles Standish as the Visitations recorded below show.

VISITATION of 1613 by Richard St. George.

Thurstan Standish (of Duxbury) a younger brother of Standish of Standish.

VISITATION of 1664 by Sir William Dugdale.

Thurston Standish ( of Duxbury) second son of Sir Alexander Standish of Standish.

The above Visitations of 1613 and 1664 meet the statement of Lawrence Hill noted below -:

"the

similarity with Myles’ statement in his will is an extraordinary circumstance”. – Lawrence Hill

"must be the link to the House of Standish, which has been sought for centuries". – Lawrence Hil

![]()

Point 3. 1655. The Will of Myles Standish and the land he called Isle of Man.

A final observation about his will is the absolutely accurate and unambiguous naming of the Ormskirk lands, after long years away from England. This is the most decisive and revealing feature of the whole enucleation, for these properties had belonged only to the Ormskirk branch. Proof of Myles’ descent from Huan Standish of the Isle of Man is further confirmed by the name of the last estate mentioned in the will, ‘the ile of Man’.

– Lawrence Hill.

Lawrence Hill describes the Isle of Man in the year 1655 as follows.

The Isle of Man occupies a strategic position in theIrish Sea, roughly equidistant from England, Scotland and Ireland. It is about thirty miles long by ten miles wide and is an island of bays and mountains of great natural beauty. – Lawrence Hill

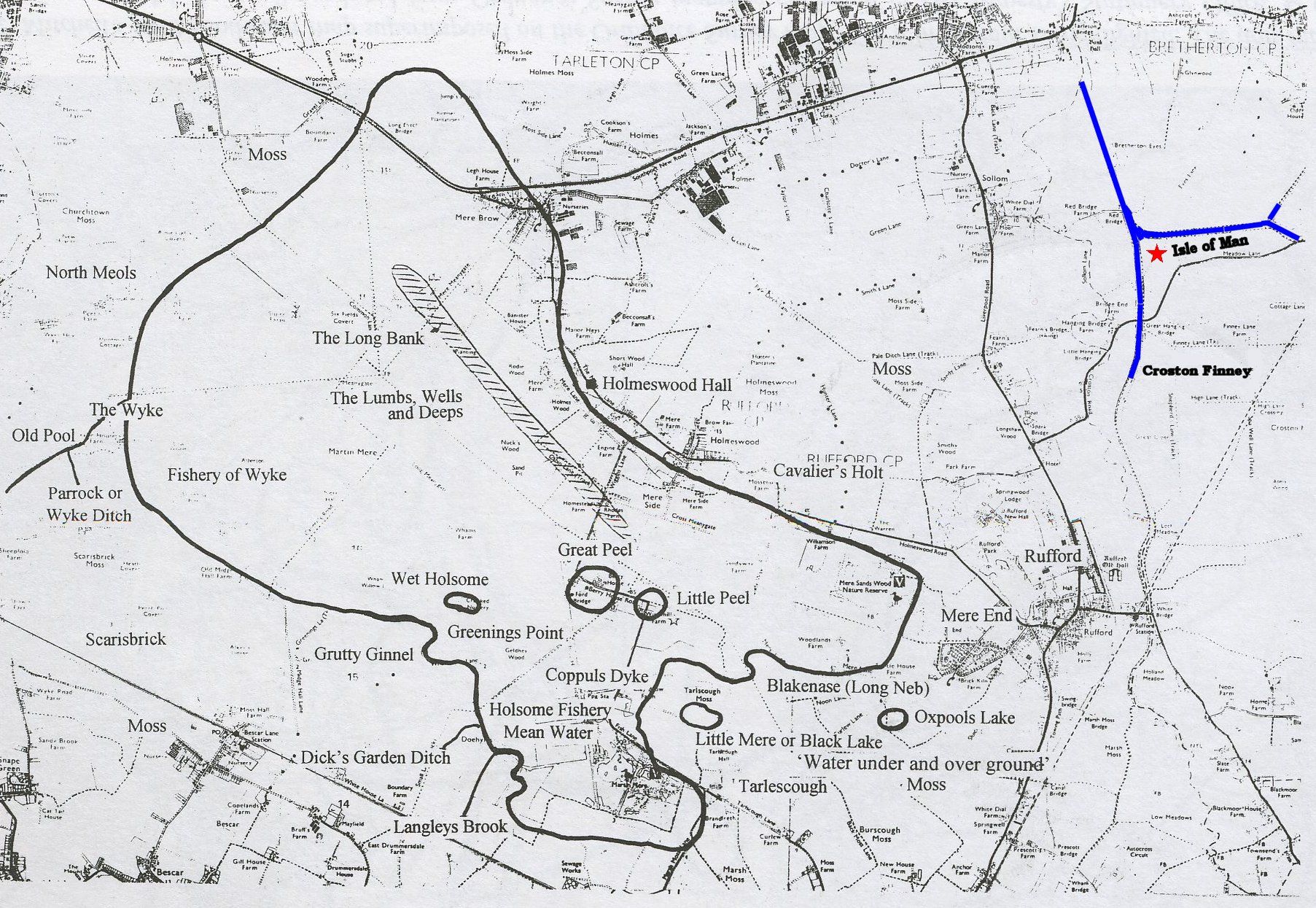

In 1655 the citizens of the Towns and Villages of Lancashire such as Chorley, Duxbury, Standish and those listed in the Will of Myles Standish – Ormskirk, Burscough, Newburgh, Mawdesley, Wrightington, Croston knew of a different Isle of Man to that in the Irish Sea, a small area of land situated on the boundary of the village of Croston surrounded by the outflow of three local rivers the Douglas, the Yarrow and the Lostock. The area around Croston Lancashire England was very prone to flooding and large areas of land were under water for most of the Winter Months. Documents in the Lancashire Archives record the extensive drainage works carried out in the area by Victorian Engineers to drain the land for agricultural use.The proximity of Croston to the great Mere at Rufford which contained several small islands (the islands were farmed by local residents) gives an indication of the amountof land permanently under water in this part of central Lancashire. - Webmaster

Map of the MERE/Water Plain and Croston Finney.

Picture of the Croston Area showing the site of the Isle of Man 1985.

Drainage Dykes for the Mere and drainage of the general water catchments area 1850.

The Pumping Station is required to keep the land area above Water Level 1963.

![]()

The Mystical Lands in the Will of Myles Standish -

Croston - Burscough -Mawdesley - Isle of Man sit to the east of the great Mere in Lancashire.

The Great Mere at Rufford in Lancashire is famous for its reputation as the last resting place of

“Excalibur” the sword of King Arthur, held in the hand of the Lady of the Lake it was taken into the middle earth beneath the waters of the Mere to be returned to mortal man at the hour of his greatest need. On the basis of local

tradition and archaeological finds of human and animal bones and horseshoes,

which place the sites of three of Athur's battles in the area around Wigan Lancashire.

Baines quotes extensively from

Whitaker's History of Manchester (1795, vol. I): he equates 'Linnuis' with Martin Mere; repeats the local

legend that, following Arthur's battle

near Blackrod, the Douglas was crimsoned with blood as far as Wigan. Arthurian traditions

also abound in the local folklore of Martin Mere itself. It was supposedly into this lake that the

nymph Vivian, mistress of Merlin, disappeared with the abducted infant Lancelot, and here in

subterranean caverns beneath its waters, the child was

educated. There is no denying that the Mere and its

surrounding wetlands became a focus for many

of his legends. This evocative, mysterious and

extensive tract of water would inevitably attract Arthurian tradition. A

more speculative point would be - some

of these myths contain shadows of even older beliefs. Those concerning

Arthur's sword, and the nymph Vivian disappearing into the lake with the infant Lancelot, might conveniently

mask earlier folk memories of gifts

to a heathen fertility goddess or even human sacrifice. Some of the bog bodies of North Meols

Moss and other places near

the Mere suggest pagan practices. Pagan customs clung on for a long time in Lancashire. In the

nineteenth century Beltain fires were

still lit on All Hallows' Eve (31 October)

- Webmaster

![]()

Lancashire County Archives Preston Lancashire England.

Listed below are some of the many documents relating to the drainage of the water catchment around Croston / Isle of Man and the Mere.

CROSTON - GENERAL.

[from Scope and

Content] DDHE 71/19 - 28 Croston

Drainage Rate Assessment Books.

FILE - ref. DDHE 71/4 - date: 9 Sep. 1803

[from Scope and

Content] Case and Opinion of Samuel Romilly, respecting the

conduct of the Commissioners under the Croston Drainage Act.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/12 - date: 22 Nov. 1912 - 21 Apr. 1914

[from Scope and

Content] Schemes of T.R.Wilton of Liverpool for Croston Drainage

FILE - ref. DDHE 71/19 - date: 1800

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.1.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/20 - date: 1803

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.3.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/21 - date: 1806

[from Scope and Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment

Book. No.6.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/22 - date: 1807

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.7.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/23 - date: 1809

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.9.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/24 - date: 1810

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.10.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/25 - date: 1811

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.11.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/26 - date: 1816.

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.17.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/27 - date: 1817

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.18.

FILE ref. DDHE 71/28 - date: 1818.

[from Scope and

Content] Croston Drainage Rate Assessment Book. No.19.

SIR THOMAS DALRYMPLE HESKETH.

Correspondence.

FILE ref. DDHE 77/23 - date: 24 Nov. 1806 - 26 Apr. 1810

[from Scope and

Content] Correspondence with G.A. Legh Keck esq., of Stoughton

Grange, concerning the division of Tarleton Moss, and Croston Drainage.

FILE ref. DDHE 77/24 - date: 5 Jan. 1807 - 30 Nov. 1810

[from Scope and

Content] Correspondence with G.A. Legh Keck, concerning Croston Drainage and Courts and

water-courses in Tarleton.

MARTIN MERE.

An original bundle labelled "Martin

Mear".

FILE - "Observations on the

Low Lands, Drains and Watercourses in the Croston Drainage" by William Miller.

- ref. DDHE 86/2 - date: Feb. 1823

FILE - Correspondence - to Sir

Thomas Dalrymple Hesketh from Edward Forshaw, Clerk to Croston Drainage Commissioners, and William

Miller, Preston - concerning Croston Drainage, and drainage in

Bretherton and Rufford. - ref. DDHE 86/3 - date: Dec.1823 - 13 Sep. 1827

FILE - Letter: William Shakeshaft

to Robert Holmes of Preston - concerning scheme for Croston Drainage. - ref. DDHE 86/4 - date: 13 Mar. 1823

FILE - William Miller's Report on

the works necessary to complete the objects of Croston Drainage Act. - ref. DDHE 86/5 - date: Mar. 1823

FILE - Memoranda of motions

relating to Croston

Drainage. - ref. DDHE 86/5a - date: c. July. 1823

FILE - ref. DDHE 86/14

[from Scope and

Content] Circular letter, signed by Sir T.D.Hesketh, Rev.

Streynsham Master, J.Brettargh (for John Trafford, esq) and Robert Norris --

complaining of mismanagement by the Commissioners of Croston Drainage, with memoranda of

complaints.

FILE - List of principal

proprietors in Croston

Drainage. - ref. DDHE 86/18

MAWDESLEY - GENERAL.

An original bundle labelled

"Mawdesley".

FILE - "Sundry damages done

to lands in Mawdesley by the Croston Drainage and Worthingtons

leasehold". - ref. DDHE 87/30 - date: 29 July. 1819

MAPS and PLANS.

Large Maps and Plans

FILE - Plan of Croston Drainage. - ref. DDHE 122/35 - date: 1845

CROSTON Parish

Creator(s):

Church of England, Croston Parish, Lancashire

Drainage

FILE - Copy of "Mr. Bootle's written answer" to a proposal concerning Croston drainage - ref. PR2622 - date: 24 Feb. 1792

![]()